As the seasons change over from summer to autumn, the soybean fields nearest our offices in Illinois and Iowa have just begun to drop their leaves. The late planting across the Midwest has pushed harvest back and could affect yields. In next quarter’s newsletter, once harvest has been completed, we will be presenting an in-depth look at this year’s supply story with the help of an esteemed guest writer, Dr. Scott H. Irwin from the University of Illinois.

Despite the late start, we are seeing combines in fields, trucks lining up at grain elevators, and we expect this newsletter will be arriving in your mailboxes as harvest gets into full swing. As is the question every year, under what market conditions will U.S. farmers be selling their grain? Despite the 2019 supply side issues we’ve mentioned, the answer to that question for soybeans may lie more in the global demand story.

To set up that demand story, we must briefly cover the supply issues. USDA’s Economic Research Service forecasted a nearly 20 percent decline in the projected 2019 soybean harvest due to reduced year-over-year plantings and lower yields, and we have heard from a number of operators who feel the USDA estimates are optimistic. Typically, a reduction of that magnitude would constrict supply and push prices upwards, at least somewhat, but prices haven’t responded as much as would be expected. Some of that muted effect is due to the previous year’s record carryout in the soybean stock that undoubtedly assures more-than-adequate supplies.

However, you probably don’t need us to tell you that the real story on pricing, now and going into 2020, is global demand for U.S. soybeans and the effects that tariffs have had on that demand.

We all have been in enough coffee shops and grain elevators around the country this year to know

that bringing up tariffs is a charged subject. We aren’t here to discuss the possible merits of the U.S. tariffs on China and the potential benefits or disadvantages they have for the U.S. as a whole. Our objective today is to specifically look at China’s retaliatory increase in the tariffs on soybeans and the decrease of soy purchases by China and the effect it has had on the demand for U.S. soy products.

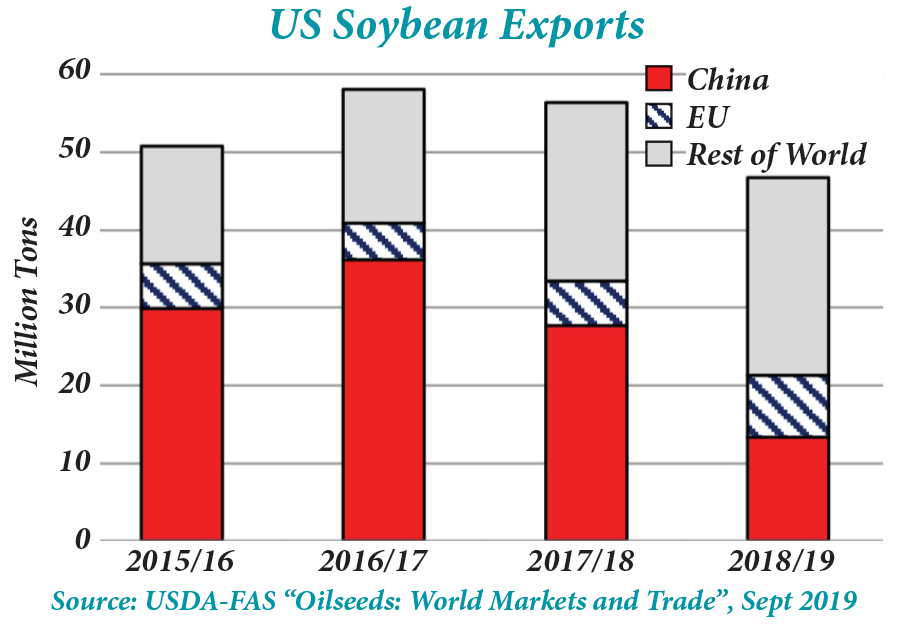

The Chinese tariffs have resulted in a substantial decrease in soybean exports for the U.S. Since 2017, there has been a 67% decline in U.S. soybean exports to China. Even with this 21.7M metric ton decrease over the past two years, China remains the largest importer of U.S. soybeans, leaving U.S. farmers exposed to potential continued demand softening in the face of an ongoing trade war. While drop-off in U.S. soybean exports to China has been partially mitigated by increased exports to other purchasers, primarily Egypt, Pakistan, the E.U. and Argentina, the overall decline in demand for U.S. soybeans has reverberated throughout the market.

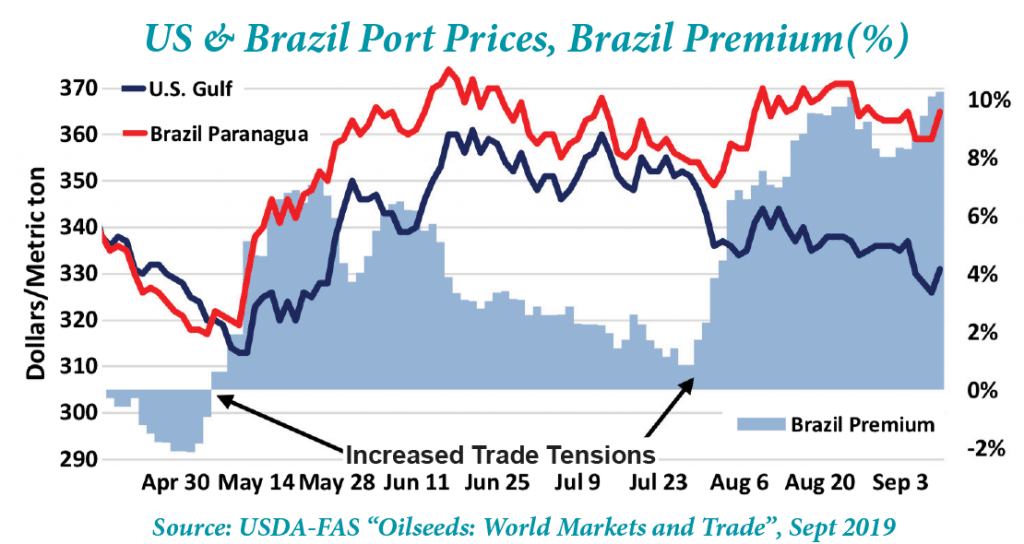

The biggest benefactor of China’s tariffs on the U.S. so far has been the soybean producing nations of South America. Brazil has seen exports and prices both rise during the tenure of China’s tariffs on U.S. soybeans. It would appear the tarrifs have created a large premium on export soybean prices for Brazil compared with that of the U.S., with premiums up to $1.35 per bushel.

Argentina, the next largest soybean producer in South America, has also seen greater exports to China. However, their exports to China are still dwarfed by those of the U.S. during the period in which tariffs have been in place mainly due to high Argentinian export taxes imposed by their own government as well as reduced yields in the recent growing season due to drought.

Further complicating the global trade of soybeans is the emergence of African swine fever (ASF) in China, a disease that will kill an infected animal within ten days. Rabobank approximates that China’s pig herd has been reduced by anywhere from 20 – 70%. According to a CNBC report, China suspects the use of food waste as animal feed as the most likely cause of ASF. Moving forward, China has banned the use of food waste, meaning that farmers are now switching to more standardized food sources, mainly grain products. This policy will likely have a positive impact on Chinese demand for soybeans as herd size recovers. While the immediate future is murky, the new food source regulations that are being put in place could eventually be positive for U.S. farmers, as China’s soybean demand could continue to grow as herd sizes are replenished.

The demand side of the pricing equation is changing every month as China looks for alternatives to U.S. soybeans. That being said, there are many factors that could trigger a rapid change in the demand story for U.S soybeans, causing a positive impact on prices. Trade frictions could lessen. China could agree to buy more ag products as a show of good faith. South America could be facing unfavorable economic headwinds.

Alternatively, any demand factors that positively affect the price of soybeans, such as those mentioned above, may only be short lived. For a long-term change to the demand of soybeans to take place, a lasting trade deal will likely have to be reached. If and when that will happen is anyone’s guess. As for how the demand story will affect the U.S. market over the next year, we will likely see another decrease in soybean acreage planted next year if a trade deal hasn’t been reached by spring, as many operators remain wary of the potential outcomes of putting money in the ground and hoping for a deal.

Beyond next year, the effects of Chinese tariffs are still unknown. It is likely that in the event the tariffs are removed that China would buy more U.S. soybeans, but there is also the potential for continued increase trade with South American countries meaning U.S. exports may not retrace their previous highs. It is also possible, however, that as part of any trade deal reached with China there is a mandatory amount of soy products they would have to buy from the U.S., in which case U.S. exports could rise to a level not yet achieved. Essentially, we will wait alongside the U.S. grain farmer to see how this plays out politically and economically, hoping for favorable resolution while also preparing for prolonged uncertainty.