By Eric L. Sarff

For my first commentary at MWA, I thought it important to touch on trends I’ve seen recently in the Midwest farmland market and the reasons behind those trends.

Trend 1: Midwest land prices have remained steady so far in 2019, despite numerous obstacles for farmers. It remains to be seen what kind of effect the delayed planting season will have on the land market. While commodity prices have rebounded recently, it’s uncertain how much of a positive effect those increased prices will have on the bottom line for operators. The main reason for the uncertainty is that poor planting conditions in the Corn Belt have seriously hampered the ability of Midwest farmers to put in their crops. At this point, it seems likely that 2019 yields will be down relative to the last few years.

Additional headwinds this year for farmers include higher interest rates, tightening credit markets and trade concerns. All these variables could influence 2019 farm incomes, which could in turn affect the land market since the financial strength of farmers determines how much they can spend on land purchases and farm rents.

For farmers who are able to produce a decent crop and capture increased crop prices, 2019 could be a profitable year. On the flip side, many operators will rely on insurance payments for poor yields or no crop at all, and those individuals may hope to just break even.

Trend 2: Overall sales volume has remained firm, but the availability of Class A farms continues to be scarce. While I have seen a steady volume of sales, they mostly have been lesser-quality farms that typically sell for a lower price. However, when we have had a “Cadillac” farm come on the market, it still commanded a premium. I have seen sales north of $12,000 per acre in Central Illinois, both at public auction and in private transactions, and competition for these types of farms remains strong. As the soil quality of a farm decreases, so does the price and the buyer interest. If the trajectory of the land market continues to trend positively, I think you will see more Class A farms come on the market from landowners who have been sitting on the sidelines looking to capture higher prices.

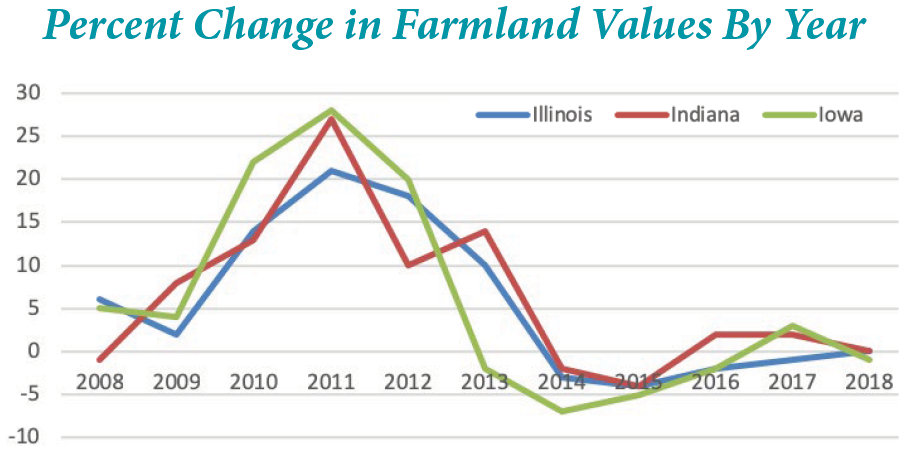

Trend 3: Increased institutional investment from previous years. I wouldn’t say 2018-19 has been as active for institutional investors in the Midwest as it was in the boom years of six to 10 years ago. But there has been a marked increase in sales volume in which an institutional or high-net-worth investor has been the purchaser. A few of these buyers are new to farmland, but most are either long-time investors who have increased their rate of acquiring Midwest row crops, or purchasers who have jumped back into the asset class after a multi-year hiatus. These investors have been purchasing for a number of reasons, from simply needing to place available funds to a changing outlook on Midwest farmland that has led them to view it more positively as an investment vehicle than they had in the previous few years. Most institutional buyers are seeking long-term investments in high-quality land, and due to the decreased public availability of this asset, many of these investors are looking at off-market transactions — which leads me to my final trend: the sale-leaseback.

Trend 4: Increased sale-leasebacks. As commodity prices have fallen over the last few years, and profit margins have tightened, many farmers have looked for ways to generate cash. One way that owner-operators have done this is to sell a tract of land to an investor and lease that farm back, typically on a long-term lease. I have worked with a number of farmers and investors on this type of transaction this year, and it can be a “win-win” for both parties when structured correctly. The buyer/investor is able to purchase a high-quality farm that has the ability to meet return-on-investment requirements, and more than likely would not have been available to them otherwise. The seller/farmer continues to operate the farm and, in many instances, will be given the right to repurchase the tract in the future, or will be given a right of first refusal. Farmers are able to keep their economies of scale intact for input costs.

A sale-leaseback transaction isn’t necessarily a sign of distress in a farming operation. In many instances, savvy operators will use it to grow their operations. For example, if a tract closer to the farmer’s core operation comes up for sale, the farmer could sell a farm farther away to an investor, lease that farm back, and use the cash generated to purchase the closer farm.